Refugees

There's been something in the apiary that I've been putting off. Dealing with some queenless bees. I don't mean the colony of the late Queen Jasmine, but rather a colony which started out as an unexpected "cast" swarm from the Copper Hive at the beginning of June. They settled in my long suffering neighbour's plum tree, whereupon I was able to collect them by shaking the branch over my skep.

This happened at a time when the apiary was full and I had more colonies on my hands than I knew what to do with, so at an early stage I united this little cast swarm with a group of angry bees from Queen Honey's former colony, in the hope that the new queen would be a civilising influence. It didn't work out that way. The colony ended up queenless.

With no queen and no egg from which to raise a new one, a honey bee colony will almost certainly die. A mated queen is needed to lay the fertilised eggs that provide the supply of worker bees that maintains the colony population. And queenless colonies are notoriously aggressive. They are not happy. Who can blame them? But they do have a trick up their sleeve. In the absence of brood pheromone, which is made by worker bee larvae in a queenright colony, the ovaries of the adult worker bees start to develop. And after prolonged queenlessness, the workers begin to lay eggs. These are unfertilised eggs so they develop into drones - male bees - rather than workers. Drones leave the hive to mate, thereby providing the colony with a last ditch attempt at casting its genes into the next generation. So the queenless workers will produce what drones they can and then they will die. Worker bees in summer live a couple of months, that's all.

What this looks like in practice is a bit of a mess. An angry, unsettled group of bees. No real brood nest. Eggs all higgledy piggledy, scattered in clumps around the walls of cells or dropped into pollen - unlike the regular and neat laying pattern of a queen, who deposits a single egg at the bottom of a perfectly prepared empty cell, every time. Among the chaos of the queenless nest, some randomly scattered drone larvae manage to survive. So I read the signs and I knew my bees were queenless.

The received wisdom for dealing with laying workers is "shake them out at the edge of the apiary". That is, dismantle the hive, carry the parts away and shake the bees on to the ground.

So a few weeks back, I went out to see them with the thought of doing this. Well, let me tell you, it is easier said than done. The queenless bees had not been idle. They'd been foraging for all they were worth, and the brood box was so full of honey that it was unliftably heavy. And there were lots and lots of bees. Every frame was coated in bees. Innocent bees! But also, bees who had nothing to lose and who would be sure to devote the remainder of their lives to stinging me. Anyway, shaking all those bees out was more than I could manage either physically or mentally.

So I came back a bit later and tried something else. I transferred about half the frames into a new box, so that I could (just about!) carry the weight, and moved them to the other end of the garden. I put a clearer board on top, designed for clearing bees from a super of honey when you want to take it from a hive. It's a wooden board with a hole in it and an array of funnelled exits that the bees can find their way out of but have a hard time finding their way back in through. I set this on top of the moved brood box, thinking the bees would come out and fly away and not find their way back. Well, it might work with supers but it doesn't work with brood boxes. Most of the bees stayed put. And the ones that came out mostly did find their way back in. I was no further forward. In fact, now I had two boxes of angry bees rather than one.

Well, I ended up just leaving them like that for the past few weeks, unwilling to take more drastic action.

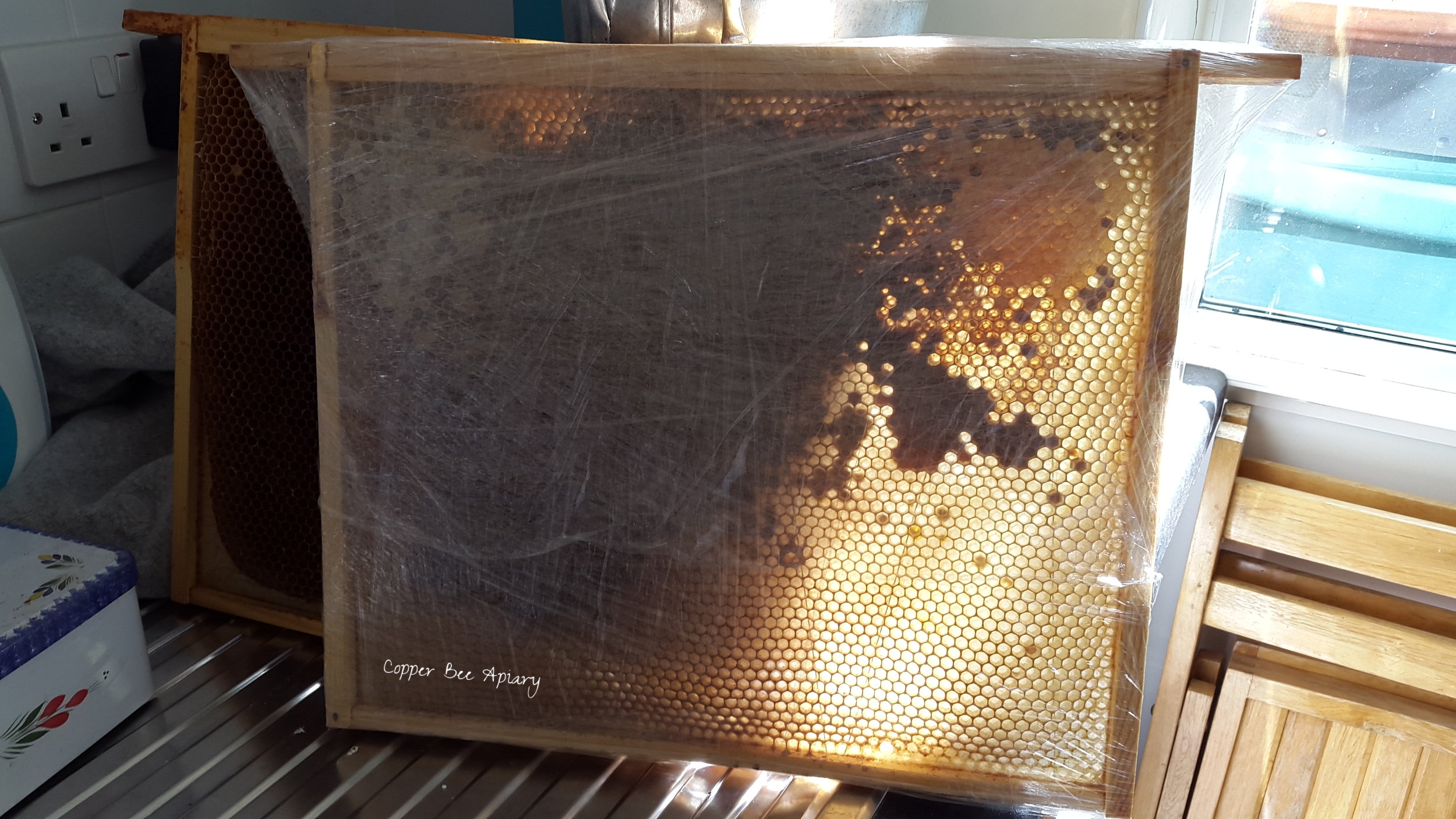

Until today. Today I grasped the nettle and decided to re-attempt the shaking out. I knew that the colonies would be weakening as more and more of the bees reached the end of their natural lives. And they were living on honeycombs containing honey and pollen which I wanted to recover as winter supplies for my other colonies.

I wasn't sure what I'd find when I opened those hives. I was rather afraid I had left it too late, and that the weakened colonies would have been over-run by other creatures that are drawn to honeycomb...wasps, ants, mice, wax moth...would the brood boxes be a horrible writhing mass of wax moth larvae and webbing?

The brood boxes were pitifully light to lift this time. Most of the bees were gone. Those that remained were clustered around the entrances, guarding the doorway. But they had guarded it well - their stores were still there, intact and unharmed.

I did the shaking out. The bees did not seem aggressive this time. They just seemed rather lost and sad.

Some sat around in groups:

Lost bees

Others looked for where their home used to be, and landed on the neighbouring hives. Pond Hive and Copper Hive became covered in homeless bees seeking entry:

It was a sad sight on the Copper Hive landing board this evening after it began to rain - refugees who were refused entry, dying outside.

Refugees

I went inside and began the long process of cleaning and storing the hive parts.